Knowing Bachelor’s Degree Holders and Social Mobility

Introduction

Charlotte, North Carolina and Indianapolis, Indiana exhibit particularly low rates of intergenerational upward mobility when compared with the rest of the country (Chetty et al., 2014). In these cities, relatively few children from the bottom 20% of the income distribution reach the top 20% in adulthood. Meanwhile, Salt Lake City, Utah and San Jose, California exhibit much higher rates of mobility. Faced with this geographical variation in opportunity, Chetty et al. (2014) assembled a list of factors that correlate with social mobility. One correlate that they identified is “the strength of social networks” (Chetty et al., 2014, p. 1558).

Although Chetty et al. (2014) did not examine the composition of these networks, the idea that knowing the “right” people can benefit you financially is conventional wisdom. After all, building relationships with successful individuals is bound to produce lucrative opportunities, so people say. This line of reasoning appears in academic sociology as well. According to DiMaggio and Garip (2012), relationships between the advantaged and disadvantaged counteracts inequality by dispersing resources from elite social circles that would otherwise monopolize these assets. In light of such observations, my research question is, What is the association between knowing a successful, or at least well-credentialed, person (a bachelor’s degree holder for the purposes of this investigation) and social mobility?

Data

The data for this analysis comes from the General Social Survey (GSS). The GSS is a record of American social trends dating back to the 1970s (“The General Social Survey,” n.d.) and is administered by NORC at the University of Chicago (“About Our Name,” n.d.). According to the National Science Foundation (2007), the GSS provides data on “a nationally representative sample of non-institutionalized adults who speak either English or Spanish” (p. 11). Thus, the GSS is not representative of the entire U.S. population. GSS respondents have to be 18 or older; they have to be “non-institutionalized;” and they have to be able to speak either English or Spanish (National Science Foundation, 2007, p. 11). Moreover, prior to 2006, even Spanish speakers were absent from the target population of the GSS (National Science Foundation, 2007, p. 12-13).

My analysis involves a sample size of 1534 people, the total number of

GSS respondents in 1985. I am only able to analyze 1985 data because

that is the year when the variables most relevant to my research

question are available, educ1 through educ5 as well as known1

through known5. These variables come from the social network module of

the GSS, which provides information about “the people with whom [the

respondent] discussed important matters” within the past 6 months

(Smith et al., 2018). Information is available for five of the people

the respondent lists, hence the numbering scheme of educ1 through

educ5 and known1 through known5. educ1 through educ5 describe

the education level of each person within the respondent’s 5-person

network. Likewise, known1 through known5 describes how long the

respondent has known each person in their network.

Methods

My goal is to understand one direction of the relationship between knowing a bachelor’s degree holder and upward mobility: I am interested in what happens to upward mobility after one has gotten to know a bachelor’s degree holder as opposed to the inverse (i.e., encountering bachelor’s degree holders after mobility). Unfortunately, the GSS does not provide the longitudinal data needed to tackle this directly. In order to eke out a hint of directionality, I use the length of the respondent’s relationship with the bachelor degree holder they knew longest as a proxy for whether the respondent knew this person prior to achieving upward mobility. In order to do this, I assume that the longer an upwardly mobile respondent has known a bachelor’s degree holder the more likely it is that this relationship started prior to the respondent achieving mobility. (Admittedly, I have no way of ascertaining from the GSS whether the bachelor’s degree holder actually had their degree before the respondent achieved mobility. Thus, for conciseness, I will use the term “bachelor’s degree holder” to refer to individuals who had a bachelor’s degree prior to the respondent’s mobility as well as those who did not but did manage to obtain one by the time of the respondent’s GSS interview.) If the correlation between knowing a bachelor’s degree holder and social mobility gets stronger the longer the respondent knows this person, we would at least have circumstantial evidence that knowing a bachelor’s degree holder is related to future mobility. In light of this, I rephrase my question to the following:

To investigate this question, I created visualizations that illustrate the relationship between knowing a bachelor’s degree holder and upward mobility. For more robust results, I also created an ordinary least squares regression model and a logistic regression model so that a variety of control variables can be applied.

I created two network variables: educ and known. These variables are

named for the prefixes of the GSS variables from which they were

derived. educ is the highest education level present in the

respondent’s network. Meanwhile, known describes how long the

respondent has had contact with the most educated person in their

network. I also created a variable to quantify socioeconomic mobility.

The GSS scores the prestige of the respondent’s occupation as well as

that of the respondent’s father. As a measure of the extent of

socioeconomic mobility experienced by the respondent, I took the

difference between their score and their father’s score. This variable

is the primary response variable of my models and is akin to the way in

which Nikolaev and Burns (2014) operationalized occupational mobility.

The control variables included in my model can be divided into five categories: parental socioeconomic status, demographic characteristics, educational attainment, geography, and family structure. Parental socioeconomic status is included because those who come from families with higher socioeconomic statuses have, by definition, less room with which to advance. Thus, variables such as the father’s occupational prestige score, dummy variables for whether the father and mother have bachelor’s degrees, and dummy variables for whether the respondent considered their family income at age 16 as having been above or below the average for American families are all included in my models. Demographic characteristics such as age, sex, and race are also included. (In their analysis of college majors and occupational status, Roksa and Levey (2010) controlled for age, sex, and race.) Moreover, due to the attendant financial benefits (Oreopoulos & Petronijevic, 2013), I incorporated a dummy variable for whether the respondent has a bachelor’s degree of their own. I included geographical variables because, as mentioned previously, the work of Chetty et al. (2014) demonstrates the significant regional variation in rates of intergenerational upward mobility within the U.S., and because “geographic mobility is related to income and occupational status” (Markham, 1983). Finally, single parenthood was found to negatively correlate with upward mobility by Chetty et al. (2014).

Results

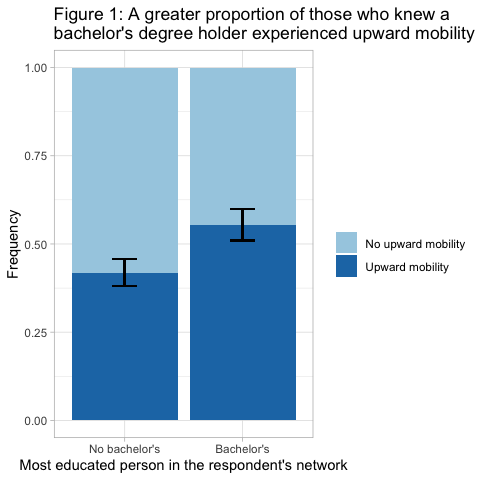

Visualizations of the data support my hypothesis that knowing a bachelor’s degree holder is positively associated with upward mobility. As can be seen in Figure 1 above, a greater proportion of respondents who knew a bachelor’s degree holder experienced upward mobility than respondents who did not know a bachelor’s degree holder. Specifically, the difference is around 0.136, and it is significant at the 0.05 level.

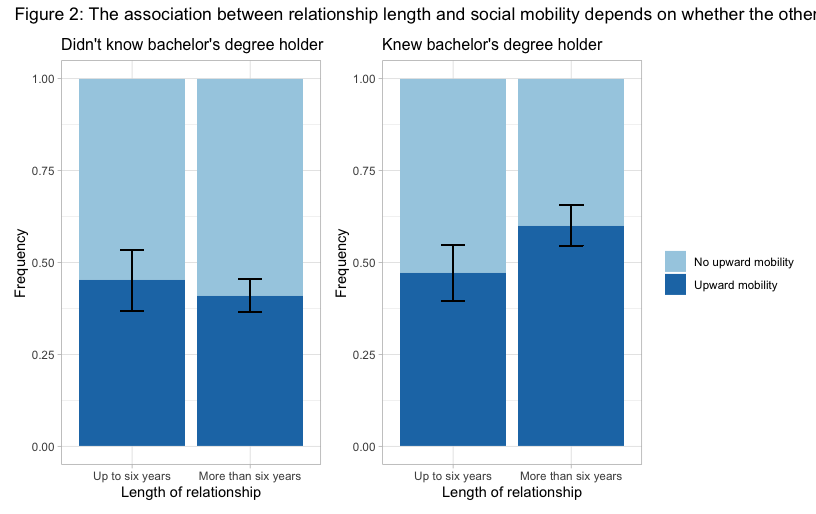

For circumstantial evidence of the directionality of this relationship, consider the leftmost plot in Figure 2. Here, I only include respondents who have a relationship with a bachelor’s degree holder. From the plot, it is apparent that a greater proportion of those who knew a bachelor’s degree holder for more than six years (who presumably are more likely to have known the bachelor’s degree holder prior to upward mobility) achieved upward mobility than those who only knew such a person for up to six years, a difference of around 0.129. However, the difference in proportions is not statistically significant at the 0.05 level, just barely missing the mark. The difference is significant at the 0.1 level though. Thus, there appears to be a positive relationship between knowing a bachelor’s degree holder for a longer period of time and upward mobility.

Perhaps simply knowing the most educated person in the respondent’s network for more than six years, regardless of whether they have a bachelor’s degree, is positively associated with upward mobility. I examine this possibility with the leftmost plot above where I focus on only those respondents who had no bachelor’s degree holders in their network. If it is the length of the relationship that matters, then I would expect a greater proportion of those who knew the most educated person in their network for more than six years to have experienced upward mobility. This is not the case. Indeed, the reverse is true, a smaller proportion of these respondents experienced upward mobility compared with those who knew the most educated person in their network for up to six years. However, the difference is not statistically significant. Thus, if they do not have a bachelor’s degree, there appears to be no difference in terms of upward mobility between knowing the most educated person in your network for over six years vs. up to six years.

Of course, no other variables were controlled for in any of the plots described thus far. These visualizations do not account for the possibility that confounding may actually be behind these findings. To address this, modeling can be used. I created two different models, an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model as well as a logistic regression model. These two models differ on the basis of their response variable. While the OLS model is intended to predict the difference between the respondent’s occupational prestige score and their father’s occupational prestige score, the logit model can be used to predict the probability that the respondent would have an occupational prestige score that is greater than their father’s. As a result of this difference in variable type, discrepancies between the two models are to be expected.

| Term | Estimate | Std. error | Statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 25.780 | 3.704 | 6.960 | 0*** |

| Knows bachelor’s degree holder | 3.673 | 1.727 | 2.127 | 0.034* |

| Knows most educated person for over 6 years | -1.240 | 1.258 | -0.985 | 0.325 |

| Father’s occupational prestige score | -0.920 | 0.036 | -25.685 | 0*** |

| Below average income at 16 | -1.123 | 1.257 | -0.894 | 0.372 |

| Above average income at 16 | 4.831 | 1.517 | 3.184 | 0.001** |

| Father has bachelor’s | -1.277 | 1.530 | -0.834 | 0.404 |

| Mother has bachelor’s | -0.364 | 1.609 | -0.226 | 0.821 |

| Age | 0.342 | 0.149 | 2.288 | 0.022* |

| Age squared | -0.003 | 0.002 | -1.997 | 0.046* |

| Is female | 0.137 | 0.778 | 0.176 | 0.86 |

| Is non-white | -2.982 | 1.432 | -2.082 | 0.038* |

| Has bachelor’s | 14.416 | 1.536 | 9.384 | 0*** |

| Lived in the south at 16 | -0.604 | 0.960 | -0.629 | 0.53 |

| Lived in rural area at 16 | -1.625 | 0.919 | -1.767 | 0.077 |

| Lived in city at 16 | 2.252 | 1.301 | 1.731 | 0.084 |

| Moved to different city in same state since 16 | 1.234 | 0.964 | 1.281 | 0.201 |

| Moved to different state since 16 | 2.181 | 0.953 | 2.289 | 0.022* |

| Single-parent household | -0.856 | 5.359 | -0.160 | 0.873 |

| Below average income at 16 and has bachelor’s | 1.447 | 2.704 | 0.535 | 0.593 |

| Above average income at 16 and has bachelor’s | -6.088 | 2.479 | -2.455 | 0.014* |

| Below average income at 16 and knows bachelor’s degree holder | -0.343 | 2.172 | -0.158 | 0.875 |

| Above average income at 16 and knows bachelor’s degree holder | -4.130 | 2.250 | -1.836 | 0.067 |

| Knows bachelor’s degree holder for over 6 years | 4.474 | 1.747 | 2.560 | 0.011* |

Figure 3: Ordinary least squares regression model output

*p < 0.05 **p < 0.01 ***p < 0.001

The output of the OLS model is shown in Figure 3. All five categories of

control variables, parental socioeconomic status, demographic

characteristics, educational attainment, geography, and family structure

are included. A term representing the square of the age variable has

been added to account for the nonlinear relationship between age and

mobility. In total, there are 23 variables in the model. However, the

variable most relevant to my research question is the interaction term

that represents knowing a bachelor’s degree holder for more than six

years. The coefficient for this variable is around 4.474 and is

significant at the 0.05 level. This indicates that knowing a bachelor’s

degree holder for over six years as opposed to any less is associated

with greater upward mobility. On the other hand, the indicator variable

for whether or not the respondent has known the most educated person in

their network for over six years is not significant. Consistent with the

visualizations above, if the respondent knows no bachelor’s degree

holders, knowing the most educated person in their network for over six

years does not significantly differ from knowing this person for up to

six years.

| Term | Estimate | Std. error | Statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.340 | 0.818 | 4.083 | 0*** |

| Knows bachelor’s degree holder | 0.091 | 0.367 | 0.247 | 0.805 |

| Knows most educated person for over 6 years | -0.659 | 0.266 | -2.474 | 0.013* |

| Father’s occupational prestige score | -0.139 | 0.011 | -12.520 | 0*** |

| Below average income at 16 | 0.015 | 0.265 | 0.057 | 0.954 |

| Above average income at 16 | 0.615 | 0.315 | 1.950 | 0.051 |

| Father has bachelor’s | -0.895 | 0.382 | -2.344 | 0.019* |

| Mother has bachelor’s | 0.391 | 0.366 | 1.068 | 0.286 |

| Age | 0.080 | 0.032 | 2.464 | 0.014* |

| Age squared | -0.001 | 0.000 | -2.240 | 0.025* |

| Is female | 0.396 | 0.171 | 2.320 | 0.02* |

| Is non-white | -0.789 | 0.317 | -2.486 | 0.013* |

| Has bachelor’s | 2.544 | 0.390 | 6.515 | 0*** |

| Lived in the south at 16 | -0.397 | 0.207 | -1.922 | 0.055 |

| Lived in rural area at 16 | -0.419 | 0.195 | -2.155 | 0.031* |

| Lived in city at 16 | 0.552 | 0.294 | 1.879 | 0.06 |

| Moved to different city in same state since 16 | 0.300 | 0.211 | 1.427 | 0.154 |

| Moved to different state since 16 | 0.378 | 0.206 | 1.833 | 0.067 |

| Single-parent household | 0.427 | 1.722 | 0.248 | 0.804 |

| Below average income at 16 and has bachelor’s | -0.601 | 0.716 | -0.840 | 0.401 |

| Above average income at 16 and has bachelor’s | -1.024 | 0.569 | -1.801 | 0.072 |

| Below average income at 16 and knows bachelor’s degree holder | 0.017 | 0.481 | 0.035 | 0.972 |

| Above average income at 16 and knows bachelor’s degree holder | -0.785 | 0.483 | -1.628 | 0.104 |

| Knows bachelor’s degree holder for over 6 years | 1.266 | 0.381 | 3.324 | 0.001*** |

Figure 4: Logistic regression model output

*p < 0.05 **p < 0.01 ***p < 0.001

I also ran a logit model using the exact same covariates as the OLS model. In the model output shown in Figure 4, the coefficient on the interaction term is positive (like the OLS model), but the p-value is even smaller than the OLS model. Indeed, it is significant at the 0.001 level. On the other hand, there is a significant negative coefficient associated with knowing the most educated person in the respondent’s network for more than six years. Thus, if the respondent does not know a bachelor’s degree holder, knowing the most educated person in their network for more than six years is negatively correlated with social mobility. This contradicts both the OLS model and the visualizations, both of which indicated that if the respondent’s network lacks a bachelor’s degree holder, knowing the most educated person in their network for over six years is not associated with social mobility.

Despite their differences, the OLS and logit models agree that knowing a bachelor’s degree holder for more than six years is associated with greater upward mobility than knowing them for up to six years. This is circumstantial evidence that part of the positive relationship between knowing a bachelor’s degree holder and social mobility stems from knowing the bachelor’s degree holder prior to mobility. I also ran the OLS model with only the occupational prestige score of the respondent as the response variable as opposed to the difference between child and father. Results were consistent between the two response variable specifications including the significant positive coefficient on the interaction term.

Discussion

My analysis suggests that having a relationship with a bachelor’s degree holder is associated with social mobility. It also provides circumstantial evidence for the directionality of this relationship. These results are consistent with papers on bridging social capital/cross-class ties. Literature on this subject show that relationships that unite people from unequal backgrounds improve the outcomes of the less advantaged in terms of income/occupational status (Kanas et al., 2011; Lancee 2010; Lancee, 2012; and Zhang et al., 2011) as well as educational achievement (Lessard and Juvonen, 2019).

That said, my findings are not indicative of a casual link between knowing a bachelor’s degree holder and social mobility. Although I used controls, my analysis remains correlational. Furthermore, a significant portion of the 1985 sample of the GSS were not included in my models on account of missing values. Indeed, my OLS and logit models use only around 61.93% of the sample. Finally, to produce my measure of occupational mobility, I only had access to the occupational prestige score of the respondent’s father. According to Beller (2009), ignoring characteristics of mothers when analyzing mobility may produce inaccurate results.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Christopher A. Bail and Devin J. Cornell for their help on this project.

Editor’s Note: This blog post has been edited since its initial publication date of June 14, 2022.

Bibliography

“About Our Name.” NORC at the University of Chicago, https://www.norc.org/about/Pages/about-our-name.aspx. Accessed 23 Oct. 2020.

Beller, E. (2009). Bringing intergenerational social mobility research into the twenty-first century: Why mothers matter. American Sociological Review. 74(4), 507-528. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240907400401

Chetty, R., Hendren, N., Kline, P., & Saez, E. (2014). Where is the land of opportunity? The Geography of intergenerational mobility in the United States. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 4(129), 1553-1623. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju022

DiMaggio, P., & Garip, F. (2012). Network effects and social inequality. Annual Review of Sociology, 38, 93-118. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102545

The General Social Survey. NORC at the University of Chicago, https://gss.norc.org. Accessed 23 Oct. 2020.

Kanas, A., van Tubergen, F., & Van der Lippe, T. (2011). The role of social contacts in the employment status of immigrants: A panel study of immigrants in Germany. International Sociology, 26(1), 95-122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580910380977

Lancee, B. (2010). The economic returns of immigrants’ bonding and bridging social capital: The case of the Netherlands. International Migration Review, 44(1), 202-226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2009.00803.x

Lancee, B. (2012). The economic returns of bonding and bridging social capital for immigrant men in Germany. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 35(4), 664-683. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2011.591405

Lessard, L. M., & Juvonen, J. (2019). Cross-class friendship and academic achievement in middle school. Developmental Psychology, 55(8), 1666-1679. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/dev0000755

Markham, W. T., Macken, P. O., Bonjean, C. M., & Corder, J. (1983). A note on sex, geographic mobility, and career advancement. Social Forces, 61(4), 1138-1146. https://doi.org/10.2307/2578283

National Science Foundation. (2007). The General Social Survey (GSS): The next decade and beyond. National Science Foundation. https://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2007/nsf0748/nsf0748.pdf

Nikolaev, B., & Burns, A. (2014). Intergenerational mobility and subjective well-being—Evidence from the general social survey. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 53, 82-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2014.08.005

Oreopoulos, P., & Petronijevic, U. (2013). Making college worth it: A review of research on the returns to higher education (NBER Working Paper No. 19053). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w19053

Roksa, J., & Levey, T. (2010). What can you do with that degree? College major and occupational status of college graduates over time. Social Forces, 89(2), 389-415. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2010.0085